Building a new product is hard. Building a successful new product is even harder. And building a profitable new product is the greatest challenge! To make things even more interesting, the fundamental customer requirements for a product change as the product and market mature. The very things that are required for success in an early stage product will hinder or even prevent success later on.

Markets, technologies and products go through a series of predictable stages. Understanding this evolution – and understanding what to do at each stage! – is vital for navigating the shoals of building a successful and profitable product.

Technology Adoption Lifecycle

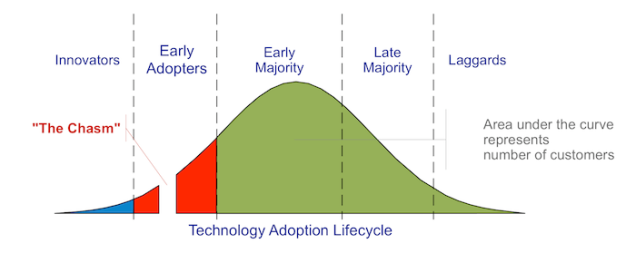

In 1991 Geoffrey Moore revolutionized technology marketing with his seminal book Crossing the Chasm. This book changed the perception of market growth from a smooth curve to a curve with a large hole. The idea was that there were major differences between early adopters of a technology and mainstream users – and that this difference is so large that there is a chasm between these groups.

Key to the Chasm Model is the idea that early adopters have completely different requirements and expectations than mainstream users. These differences are so large that completely different approaches are required. The things that produce success when dealing with innovators and early adopters will fail with mainstream users. The things that mainstream users require are of little interest to innovators.

Just to make things interesting, new markets start with innovators – without innovators you have no starting point for developing and proving new technologies. Mainstream users, on the other hand, will not adopt new, unproven products and technologies.

Innovators are seeking competitive advantage. They want new capabilities that let them leapfrog several steps ahead of their competitors. They are willing to take risk. They want something that no-one else has, and they want it now. Their metrics are capabilities, features, and time to market. They are willing to accept the chance of failure to gain the chance of success. Innovators are willing to do a lot of work themselves and to accept point solutions.

The majority of the market, on the other hand, is seeking mature products. They expect things to work out of the box. They are looking for proven solutions that they can integrate into their existing environment. They want support, upgrades, and even documentation. They are not willing to accept significant risk.

Part of Moore’s argument is that a product or technology that is successful in the innovator and early adopter markets can create enough momentum to become a defacto standard in the mainstream markets – that success in the early markets has the potential to lock competitors out of the lucrative mainstream markets.

If you are prepared for the Chasm, your goal is to cross the Chasm, establish a beachhead in the majority market, and then build out from this beachhead to conquer the profitable majority markets.

Another possible outcome is for a competitor who is already established in the majority markets to keep a close eye on new entrants into the market. As long as they are in the Innovator and Early Adopter phases they can be monitored with no action taken. When someone successfully crosses the chasm and establishes a beachhead they are vulnerable – at this point a fast follower can swoop in, use their greater resources to address the needs of the majority markets, and take over just as the market becomes profitable.

The challenge for a fast follower is judging where the new entrants are. Move too early while the market is still Early Adopters and you waste resources on people that don’t care about your strengths. Going after a market entrant who hasn’t established a proven beachhead and started to move beyond it and you may waste resources on an unproven market. Or move too late, after a new entrant has established their beachhead and moved into majority markets, and you can find yourself facing an entrenched competitor with adequate resources and newer technology and products.

Of course, there is a lot more detail than this – see the book!

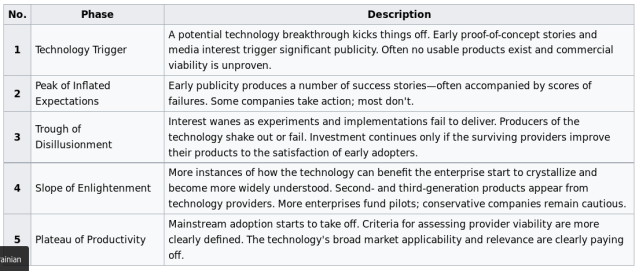

Gartner Hype Cycle

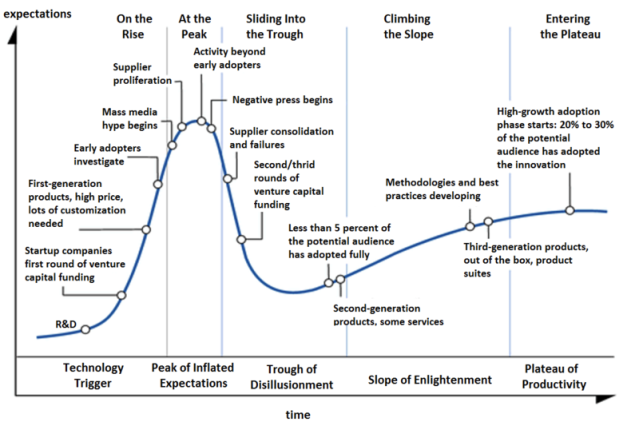

Exciting new technologies are exactly that – exciting! This excitement and inflated expectations for a new technology are often taken as proof of a large market just waiting for new products.

The Gartner Hype Cycle shows what actually happens. The Hype Cycle looks at customer expectations and perception as a technology is introduced and then matures over time.

The Gartner Hype Cycle is critical for understanding the difference between excitement and revenue. As a general rule, the more a new technology is covered in media, conferences, and even airline magazines, the lower the current real market opportunity.

To fully understand and appreciate the Hype Cycle, see Mastering the Hype Cycle: How to Choose the Right Innovation at the Right Time.

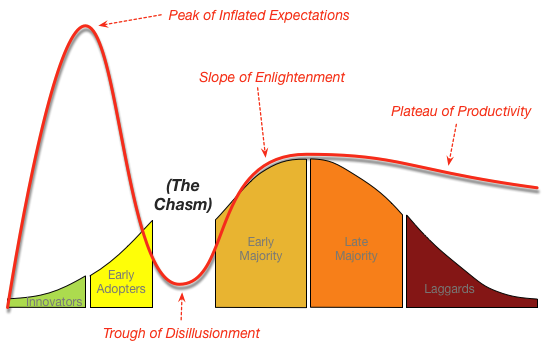

Bringing the Pieces Together

Now let’s bring these two models together:

This illustration shows that the greatest excitement around a new technology – the greatest hype – occurs before the profitable market emerges. The innovators represent about 2.5% of the total market and the early adopters another 13.5% – meaning that about 16% of the total market exists before the chasm.

This chart explains why innovation and excitement typically don’t directly lead to large revenues – there simply aren’t enough of the innovators and early adopters, and the majority markets will not accept early stage technology and immature products.

Next: Unknowable Markets

Pingback: Innovation | techponder

The “Crossing the Chasm”, “Inside the Tornado”, “Innovator’s Dilemma” and “Mythical Manmonth” need to be required reading for every computer science student. [Of course I expect they will use the same terms every other group uses of ‘this time is different’, ‘we are going to disrupt the market’, etc etc.] I found that those books have been better indicators of what technologies work, which one’s don’t and why they didn’t.

[On a side note.. I wish Moore had written a book on Monkeys in the Trees.. as that is the one section of Inside of the Tornado that most companies are in but everyone wants to focus on being Ape #1.]

Stephen, great list! Should probably also include Innovator’s Solution.

The thing I don’t like about these books is that they have a strong flavor of Survivors Bias. I plan to dig into that in a future article.

Let me throw out another thought – there are three key questions: 1. Is this technology viable? 2. Does this technology solve a problem worth solving? (Note that this is determined by the market.) 3. What exactly is the problem being solved?

I agree on the ‘Survivors Bias’. If all History is written by the winners, all Business Books have much more bias towards ‘well if you follow these 10 cargo cult things we did’ wrapped up in actual working things. That said the general top level items about the Chasm, the Dilemma, the Hype do seem to have some basis on reality.

I would add “0. What is the problem you think your technology solves?” to that list at the beginning. A lot of technology gets created and then a problem gets hunted for to be solved versus the other way. I wanted to say that as a 0 as you need to know it to get 1. and 3 is actually a different one.. “3. Is the problem you are solving the one you think it is and if it is different from 0 can you solve it better now that you know?”

We are in for an interesting discussion. The next article is focused on what Christensen has to say about identifying markets/problems. To foreshadow a bit, if you understand the problem and can define the market you are dealing with a sustaining innovation, not a disruptive innovation.